Introduction

The five present medallions depict the Five Sorrowful Mysteries and all originate from a lost painting of Our Lady of the Rosary. The painting was executed in Brussels around 1500 by the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece, perhaps for a Dominican convent in the city. The work was dismembered before 1928, when all fragments were sold at auction and attributed by Max J. Friedländer to Colijn de Coter. The discovery of a photograph showing the painting in its original state allows for the formulation of new hypotheses regarding the painting's provenance and its attribution to the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece, an associate of Colijn de Coter active in Brussels around 1490–1520. The fascinating history of the painting and its fragments is directly linked with the history of collecting, in a rather unusual way: a picture shows all the fragments mounted together, imitating the composition of the original painting. If the panel was cut for monetary reasons, it does not make sense to frame all the fragments together. However, it seems even less plausible that the panel was cut simply because of the taste for fragments. Still housed in their c. 1930 frame, our five medallions have a remarkable provenance : in the 1930s, they were, along with ten other medallions, in the collection of Mme C. Van der Linden, who owned a stunning collection, including the Sacerdoce de la Vierge painted by the Master of the Collins Hours. Stylistically, the Five sorrowful mysteries at hand are a perfect example of the art production in Brussels c. 1500. They strongly evoke Colijn de Coter, as outlined by Max J. Friedländer's attribution. However, comparisons with the paintings of Colijn de Coter and of his circle, on which research has progressed, clearly point towards the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece. This artist collaborated with Colijn de Coter on at least two large altarpieces, and shows an extremely similar vocabulary, fully imbued with the masters of the previous generation, such as van der Weyden. Nevertheless, the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece differs from Colijn de Coter in his more monumental style.

We thank Prof. Frédéric Elsig, Dr. Till-Holger Borchert and Prof. Didier Martens for their expertise.

Commentary

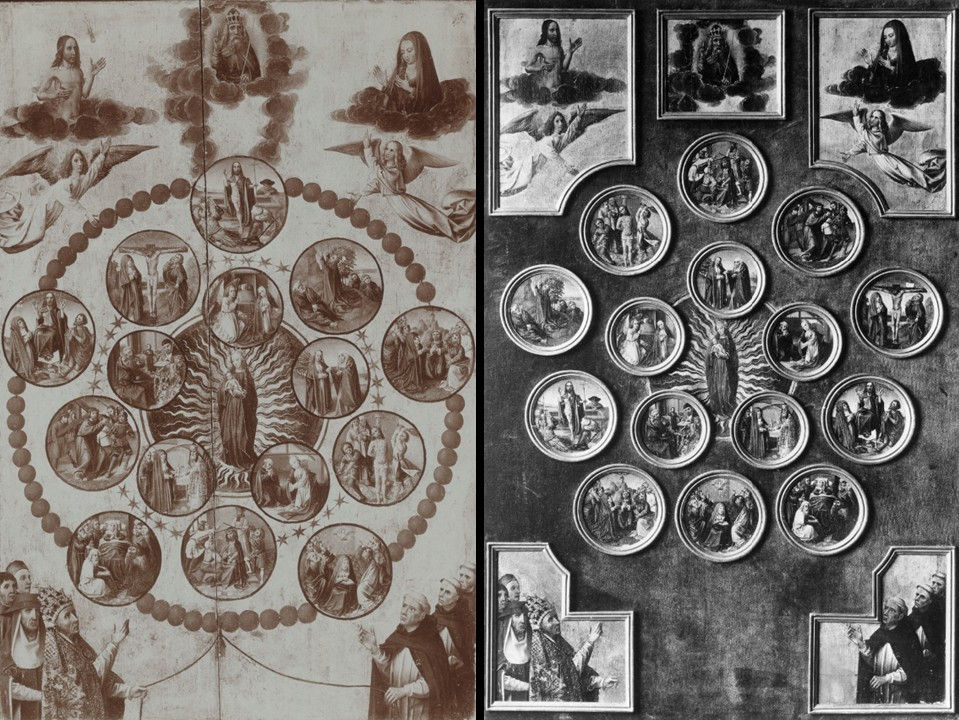

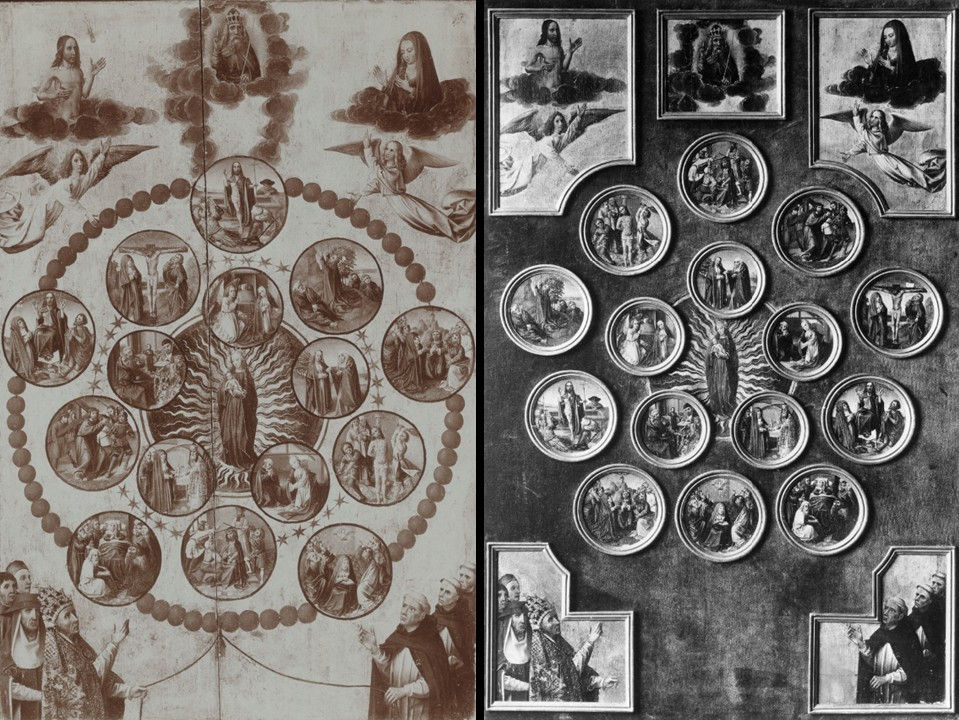

As established by the provenance of the five present medallions, their history is quite tumultuous. It is hardly understandable without having in mind the history of collecting, of taste, and of the art market. As proven by the early 1900s photography, which was, to our knowledge, never published or mentioned in any description, the painting remained in its original state until around 1900 (ill. 1.) and was dismembered before 1928, when all fragments appeared at auction (ill. 2.). This is exactly when the Old Master market was living in its Golden Age and when collectors of various kinds were actively looking to purchase fragments of artworks, as last witnesses of lost art. Commercial manipulations are mainly known regarding manuscripts, which were dismembered to sell only the pages with painting - the pages considered "interesting in art, for I don't care about old texts", to quote John Ruskin (d. 1900). However, we forget how paintings were victims of the same practice. Many paintings as we see them today are cut and have been manipulated in order to suit the taste of the trend of their times.

ill. 1. Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece, Our Lady of the Rosary, c. 1500. Photography c. 1900 | ill. 2. Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece, Fragments of a lost painting of Our Lady of the Rosary, c. 1500. Photography c. 1928.

Our five medallions are an unusual example of this: undoubtedly, the painting from which they originate was cut for profit. However, the picture showing all the fragments mounted together (ill. 2.) hardly makes sense: why dismember a painting if it is only to replace all the fragments together? One option that comes to mind would be to showcase the fragmentary state of the artwork, as fragments were, and still are, fashionable. Another hypothesis could be that they first wanted to sell the fragments together and pretended this installation was still missing pieces, so that the fragmentary state could increase the price. Or was this picture taken when the fragments were in another private collection, before the L.W.** collection in Brussels? If so, why buy a literally broken painting and not a fragment? The reason why the fragments were all placed together remains unclear, but it surely is unusual. We would except this picture to be taken nowadays, when a collector succeeds in reuniting all the fragments, but surely not right after the painting was dismembered.

Another interesting element is how the fragments were offered at auction in 1928. The fifteen medallions were separated into three lots of five medallions, and the selection of the five medallions wanted to follow the iconography of Our Lady of the Rosay (also unusual as there is no more Lady of the Rosay): the three lots tried to illustrate the three mysteries of the Rosary : 1. Joyful Mysteries (Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity, Presentation, and Christ among the Doctors), 2. Sorrowful Mysteries (Christ in Gethsemane, Flagellation of Christ, Mocking and crowning with thorns of Christ, Christ carrying the cross, Christ crucified with Mary and John) and 3. Glorious Mysteries (Resurrection, Ascension, Pentecost, Assumption of the Virgin, Coronation of the Virgin). However, in 1928 four medallions were erroneously installed in the wrong Mysteries. Christ in Gethsemane and Christ carrying the cross were switched with the Resurrection and the Pentecost. When C. van der Linden purchased all three lots (all fifteen medallions), she rearranged them in the correct order: it is therefore almost certain that the installation in which the two series of five medallions currently known dates back to when C. van der Linden owned the artworks. To our knowledge, the fragments composing the lot 24 (The Virgin in Child, The Christ and an angel, God the Father, The Virgin and an angel, The Pope, a cardinal, and two laymen, and Three Dominicans) during the 1928 sale have not reappeared since the sale and, if they have not stayed together, it is very likely that they are lost. As we can see when comparing the picture of the painting in its original state and the two pictures showing the dismembered paintings, these fragments have been heavily retouched: wood was added on some fragments (notably the central part, showing the Virgin) to make them slightly bigger, some original paint was erased. This again raises the question as to why this painting was dismembered: the fragment with God the Father was first cut in a small little square, only to be enlarged shortly after. The Rosary was erased and the fingers of the angel on the right were added, only to be cut after. Five other medallions (Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity, Presentation, and Christ among the Doctors) are also currently not located: they were seen last time at the 1937 sale in Amsterdam but have disappeared since.

To this day, the ten known medallions are not only an especially fascinating example of a commercial product that shed light on the history of the art market, the evolution of taste and the life of Old Master paintings but also the last witnesses of what must have been a special commission and an important work in the career of the Master of the Orosy Altarpiece.

The name "The Master of the Orsoy Alarpiece" appears first in 1922 (more exactly, the artist was named "Maître Bruxellois du Retable d'Orsoy", i. e., "Brussels Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece"). This artist takes his name from the double-winged Altarpiece in Sankt Nikolauskirche in Orsoy, Germay (ill. 3.), that Max J. Friedländer had attributed, in 1908, to an anonymous master in closely working with Colijn de Coter (who is responsible for the outer wings of the same altarpiece), a very important painter from Brussels working in the tradition of Rogier van der Weyden whose name is known thanks to three signed paintings (Saint Luke painting the Virgin, Paris, church of Vieure; altarpiece of the Trinity, Paris, Musée du Louvre; and the Virgin Crowned by Angels, Düsseldorf, private collection). Max J. Friedländer also attributed to the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece the Nativity with a donor and the Circumcision in Brussels (ill. 4.) and one panel, depicting the Meeting of Saint Romuald and Saint Gummarus, in the large altarpiece of the Life of Saint Romuald in Mechelen Cathedral. In 1924, Friedrich Winkler attributed the wings of the Praust Passion Altarpiece (Warsaw, Museum Narodowe) to the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece.

ill. 3. Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece, Orsoy Altarpiece (inner wings), c. 1500-1520. Orsoy, Sankt Nikolauskirche.

ill. 4. Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece, Nativity with a donor and the Circumcision, c. 1500. Brussels, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique.

In the 20th century, many art historians did not really agree with the need to define one personality that seems to be so closely related to Colijn de Coter and the attributions of the artworks to the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece were much debated. For some authors, it was more accurate to consider the whole altarpiece as "studio of Colijn de Coter", since the anonymous master was undoubtedly an "assistant" or "pupile" of Colijn de Coter. This notion of workshop is central in Catheline Périer-D'Ieteren major monograph publication, Colyn de Coter et la technique picturale des peintres flamands du XVe siècles, published in 1985. She mentioned the Orsoy Altarpiece, the Nativity in Brussels as well as the paintings from the altarpiece of the Life of Saint Romuald in Mechelen but does not develop the question of the attributions. She agrees that these altarpieces were painted in collaboration with one or more artists but does not mention the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece, even though this name was used as early as 1922.

The stylistic analysis of the works of the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece shows indeed a great proximity with Colijn de Coter. They both share the same vocabulary, mainly taken from the greatest artists of the previous generation, such as Rogier van der Weyden and Robert Campin. The way the two painters render the texture effects, with heightened plastic effects, is also very similar. However, the main difference resides in the overall aesthetic of the paintings. Colijn de Coter has a very sculptural brushstroke, with an emphasis on heavy draperies and strong treatments of lights and shadows. The Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece shows a more monumental aesthetic, with particular attention paid to a solid arrangement of the elements within the composition - and especially of the figures, which seem rooted in the composition. The colors used in the paintings by the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece are brighter and more close to works by the Master of Affligem (the Master of the Story of Saint Joseph).

The five present medallions, and the painting they originate from, show great similarity with the characteristics mentioned above. It is, however, strange that Max J. Friedländer, who himself isolated the first corpus d'œuvre of the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece, attributed these medallions to Colijn de Coter. Perhaps was he simply meaning Colijn de Coter as in "workshop of Colijn de Coter"? Perhaps did he see only the pictures of the painting, but not the painting itself? Or maybe the unusual iconography made him believe the master of the workshop must have been in charge? It is, however, enlightening to note that Max J. Friedländer did not include the medallions in his chapter on Colijn de Coter in his famous Early Netherlandish publication. Moreover, Jeanne Maquet-Tombu's paragraph on the medallions at hand and the other fragments from the lost painting is instructive: while the art historian attributes these fragments to Colijn de Coter and a pupile, she clearly links these paintings to the Orsoy Altarpiece: "[…] Le Pape et le cardinal on les traits des grandes figures d'Orsoy […] le petit format des tondi a occasionné, comme dans le bas des volets d'Orsoy, un tassement des personnages […]". It indeed seems that the most relevant comparisons can be found with the inner wings of the Orsoy Altarpiece, which shows the same monumental treatment of the figures, the same morphological details, and the same details in the layout of the composition. The Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece is today considered an important Brussels artist with his own artistic personality. He was undoubtedly trained with Colijn de Coter and was greatly influenced by him: his formulas and vocabulary are strongly indebted to the art of Colijn de Coter, but his style shows differences. The attribution of the five present medallions (and therefore of all the parent fragments) to the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece is an important new addition to the corpus of the anonymous master and helps us to define more precisely the workshop of Colijn de Coter as well as the individual artistic personality of the Master of the Orsoy Altarpiece.

ill. 5. Cornelia van Wulfschkercke. Tripartite rosary, Book of Hours, c. 1500-1510 (London, Sotheby's, November 17, 1999, lot 3).

The original destination of the now lost painting of Our Lady of the Rosary from which the five medallions at hand originate remains an question. The presence of three Dominicans on the bottom right of the painting may indicate that it was commissioned by a Dominican convent, perhaps in Brussels. However, the three Dominicans may as well be depicted on the painting as the Dominicans are the principal and most ardent propagators of devotion to the Rosary throughout Europe. During the early 16th century, depictions of Our Lady of the Rosary became more popular, also in illuminated manuscripts. Interestingly, the composition of the lost painting of Our Lady of the Rosary is very close to a Book of Hours realized in Bruges c. 1500-1510 (ill. 5.). Only the figures on the lower part of the panel painting (left: The Pope, a cardinal, and two laymen; right: Three Dominicans) are missing in the illumination, which seem to indicate that the Dominicans on the panel painting were painted not as general propagator of the devotion of the Rosary, but most probably as commissioners of the painting from which the five medallions originate.

BROWSE AVAILABLE MASTER WORKS & COLLECTIBLES FROM THE MIDDLE AGES TO TODAY